As I’ve stressed in this series, Snorri Sturluson’s Edda is our main source for what we know of as Norse mythology. And it was written to impress a 14-year-old king. That explains why Norse mythology is so full of adolescent humor—especially when it comes to sex.

The Norse gods certainly had odd love lives. According to Snorri, Odin traded a lonely giantess three nights of blissful sex for three drafts of the mead of poetry. Another lucky giantess bore him valiant Vidar, one of the few gods who survived Ragnarok, the terrible last battle between gods and giants. Odin coupled with his daughter Earth to beget the mighty Thor, the Thunder God. Of course, Odin was married all this time. His long-suffering wife, wise Frigg, was the mother of Baldur the Beautiful, at whose death the whole world wept (we’ll get to that story next week).

Njord, god of the sea, married the giantess Skadi as part of a peace treaty. She wanted to marry beautiful Baldur and was told she could have him—if she could pick him out from a line-up looking only at his feet. Njord, it turned out, had prettier feet. But he and Skadi didn’t get along. He hated the mountains, she hated the sea: He hated the nighttime howling of the wolves, she hated the early morning ruckus of the gulls. So they divorced. Afterwards, Skadi was honored as the goddess of skiing. She and Odin took up together and had several sons, including Skjold, the founder of the Danish dynasty (known to the writer of Beowulf as Scyld Shefing). Njord married his sister and had two children, the twin love gods Freyr and Freyja.

Then there’s Loki, Odin’s two-faced blood-brother, whose love affairs led to so much trouble. Loki, of course, was the reason why the giantess Skadi was owed a husband in the first place: His mischief had caused Skadi’s father to be killed. In addition to getting a husband, Skadi had another price for peace. The gods had to make her laugh. She considered this impossible. “Then Loki did as follows,” Snorri writes. “He tied a cord round the beard of a certain nanny-goat and the other end round his testicles, and they drew each other back and forth and both squealed loudly. Then Loki let himself drop in Skadi’s lap, and she laughed.”

Loki, writes Snorri, was “pleasing and handsome in appearance, evil in character, very capricious in behavior. He possessed to a greater degree than others the kind of learning that is called cunning…. He was always getting the Aesir into a complete fix and often got them out of it by trickery.”

With his loyal wife, Loki had a godly son. In the shape of a mare, he was the mother of Odin’s wonderful eight-legged horse Sleipnir, which I wrote about in part two of this series.

But on an evil giantess Loki begot three monsters: the Midgard Serpent; Hel, the half-black goddess of death; and the giant wolf, Fenrir.

Odin sent for Loki’s monstrous children. He threw the serpent into the sea, where it grew so huge it wrapped itself around the whole world. It lurked in the deeps, biting its own tail, until taking revenge at Ragnarok and slaying Thor with a blast of its poisonous breath.

Odin sent Hel to Niflheim, where she became the harsh and heartless queen over all who died of sickness or old age. In her hall, “damp with sleet,” they ate off plates of hunger and slept in sickbeds.

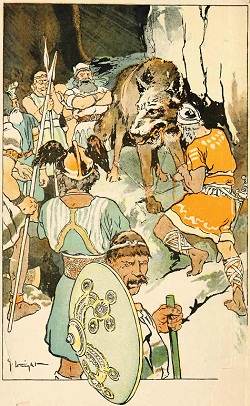

The giant wolf, Fenrir, the gods raised as a pet until it grew frighteningly large. Then they got from the dwarves a leash bound from the sound of a cat’s footstep, a woman’s beard, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird.

Fenrir would not let them tie him up until Tyr, the brave god of war for whom Tuesday was named, put his hand in the wolf’s mouth as a pledge of the gods’ good faith. The wolf could not break free of this leash no matter how hard he struggled, and the gods refused to let him loose. It had been a trick all along.

“Then they all laughed except for Tyr,” Snorri writes. “He lost his hand.”

It’s a classic Snorri line. Like the story of Skadi picking her bridegroom by his beautiful feet, and how Loki made her laugh, the story of the binding of Fenrir—and how Tyr lost his hand—is known only to Snorri. As I’ve said before, no one in Iceland or Norway had worshipped the old gods for 200 years when Snorri was writing his Edda. People still knew some of the old stories, in various versions. And there were hints in the kennings, the circumlocutions for which skaldic poetry was reknowned. Snorri memorized many poems and collected many tales. From these he took what he liked and retold the myths, making things up when need be. Then he added his master touch, what one scholar has labeled a “peculiar grim humor.” The modern writer Michael Chabon describes it as a “bright thread of silliness, of mockery and self-mockery” running through the tales. And it is Snorri’s comic versions that have come down to us as Norse mythology.

Next week, in the last post in this series, I’ll examine Snorri’s masterpiece as a creative writer, the story of the death of Baldur.

Nancy Marie Brown is the author of Song of the Viking: Snorri and the Making of Norse Myths, a biography of the 13th-century Icelandic chieftain and writer, Snorri Sturluson. She blogs at nancymariebrown.blogspot.com.

Love these little texts about Norse mythology :-)

How can you be sure a peculiar flair for grimm humour wasn’t something that was part of the Norsemen’s way? In the northen countries, the humour is grimmer than in most parts of the world by default. And I also don’t see Tyr losing his hand as funny, but it more sounds to me like a morality tale, which some folklores are. Snorri chose the way he wrote the stories (what kind of writers “voice” he used), but that in itself does not mean he made them up. The stories could still be old and true and he just wrote them in a style he found funnier or more interesting.